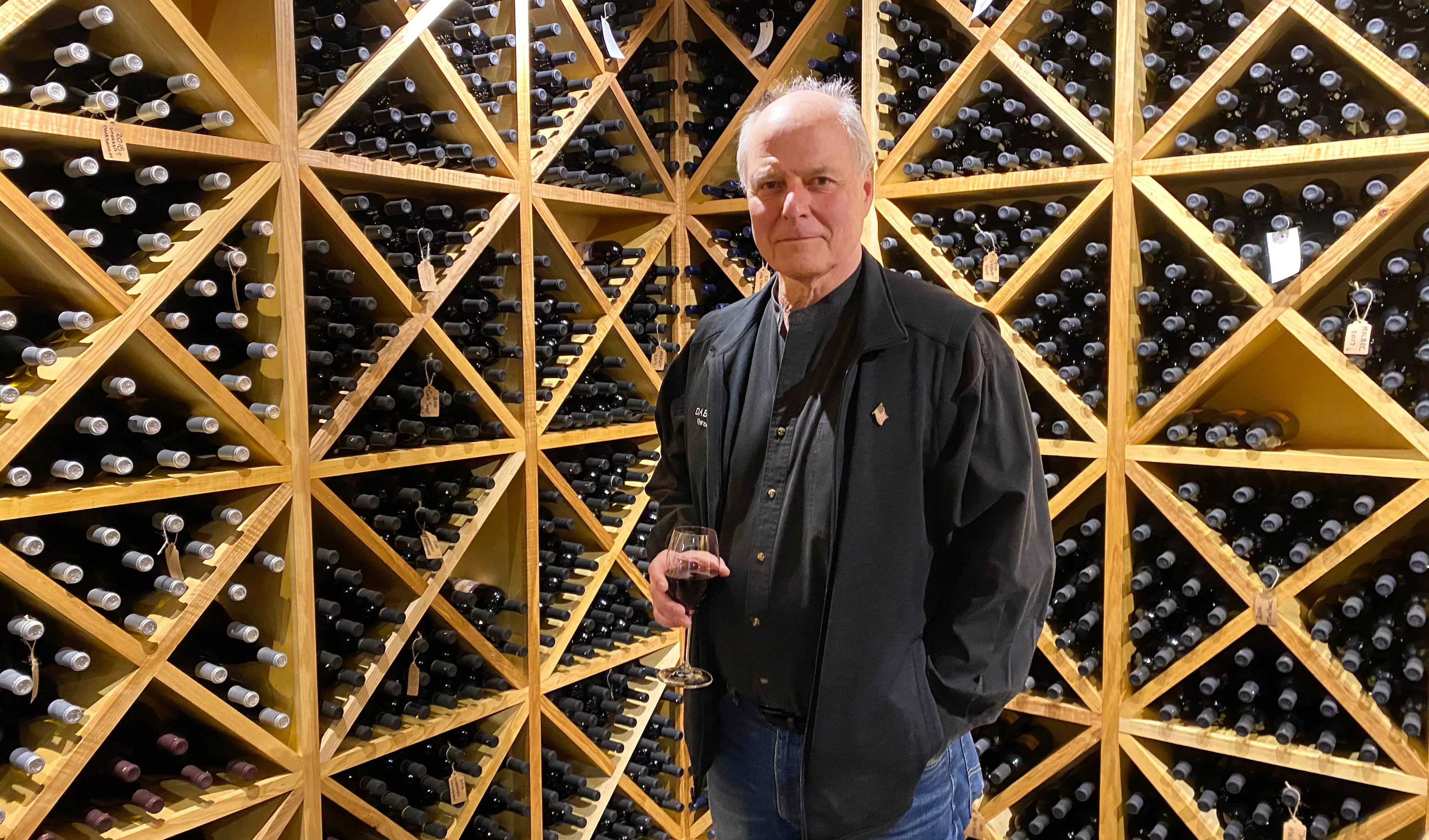

Perceptions can be difficult to change in the wine world, but that is not going to stop Dablon Vineyards and Winery owner William Schopf from trying.

From growing rarely seen grape varietals thought to be impossible to grow in Michigan, to showing customers one-by-one that great wine can be produced in the region, Schopf is determined to make Dablon part of the rising tide that lifts all boats in the Michigan wine community.

Changing the perception

While he spent most of his professional career in Chicago, Schopf said he’s had a house in southwest Michigan for about 40 years. During much of that time, he thought the views of Michigan as a subpar wine region were not unfounded.

“Historically, the wines weren’t that good,” he said. “Let’s say I was looking for a $35 bottle, and I had one from Sonoma, one from Napa, and one from Michigan. I never would’ve bought the Michigan one.”

Schopf, who in 2009 planted his first grapevines along Baroda’s glacial hillside at 111 W. Shawnee Road, has since structured his Baroda vineyard in the likeness of those found in the Burgundy and Bordeaux regions of France. He believes southwest Michigan’s unique terroir can handle most cool weather grapes, and has proven as much by growing 17 different varietals on-site.

Yet, the belief still exists that Michigan wines do not compare to those from revered regions around the world or even the United States. Wine Enthusiast Magazine even recently dropped Michigan from its review coverage.

“My biggest challenge starting this vineyard and winery is overcoming the reputation of Michigan wine as being sweet, white, and cheap,” he said. “We’re just the opposite. We’re expensive, we’re mostly dry and red – although our whites are great too.”

These headwinds, however, are not stopping Schopf and Dablon Winemaker Rudy Shafer from pushing the limits of what Michigan wine can be.

Schopf, left, and Shafer.

Nebbiolo

While Dablon features some of the more common grape varietals found in Michigan – Riesling, Pinot Grigio, Cabernet Franc and Merlot – the vineyard stands apart from others with grapes like Syrah, Tempranillo and Petit Verdot grown on-site.

“We want good vinifera wines – particularly French, Spanish or Italian,” Shafer said. “But the grapes have to grow here, too. California’s a a lot warmer climate than we have, so we can’t grow Zinfandel, for example. We have to pick cool climate grapes. That’s primarily why we’re sticking with the French model.”

One of the new grape varietals Dablon has been growing is the Nebbiolo, which traces its origins to the Piedmont region of Italy. Schopf said the winery first planted this varietal about six years ago, and it grows quite well in the southwest Michigan terroir.

“Commonly, it has been thought that Nebbiolo grapes are best grown and made into wine in the Piedmont region,” Schopf said. “Our Nebbiolo will of course not taste the same as the Nebbiolo grown in Piedmont,” Schopf said. “Perhaps it will be worse, perhaps better, but definitely different. In that regard, I think Nebbiolo has a future in the regions of the United States, such as southwest Michigan, where world-class wine grapes can be successfully grown.”

Shafer said he has not run into many problems growing any varietals they produce – at least ones that can’t be solved by integrated pest management. Both he and Schopf and Shafer credit Lake Michigan and the rich, sandy soil of Michigan’s Fruit Belt for Dablon’s ability to grow so many grapes well.

“Lake Michigan … powerfully improves our climate, slowing down bud break in the spring, holding back the frost in the fall and moderating the falling temperatures in the middle of winter,” Schopf said. “Just as importantly, we do not have the severe drought problems seen recently in Europe and California.”

The first bottles featuring the Nebbiolo will be released this summer, in the Langhe style. Schopf said 50 percent of the Nebbiolo grapes are being used for this style, which ages for about a year in European oak barrels before being bottled.

“The Langhe style Nebbiolo … has been provided to customers in our tasting room for barrel sampling,” Schopf said. “The response has been quite positive both from them and our team.”

The other 50 percent will be used for a Barolo/Barbaresco style, which needs a 25-day maceration and up to four years in European oak.

In addition to that four years, the process of getting the proper harvest from a new grape variety can take another five years. Dablon gets their red wine varietals from a nursery in California, which takes about a year before they are ready to plant in Michigan. After that, Schopf said it will take about four years before a commercial harvest is ready.

So how does the wine producer stay patient?

“The better question is, how do you stay alive long enough?” said Schopf. “We’ll see.”

‘It takes time’

Schopf said with the time-intensive process of making the wine, it can be difficult to answer the question of “Will our customers like this one in 2028 or 2029?” So, instead he focuses on two questions:

“Will it improve the reputation of Dablon, and will it improve the reputation of Michigan as being a world-class place to grow wine grapes and make world-class wines?” Schopf said. “So, we just tend to go for the best wines that they make around the world.”

Another challenge in changing the perception, according to Schopf, is getting the wines into restaurants and stores across the region. Right now, he said they have wholesale distributors in Michigan, Indiana and Illinois.

“That has been the biggest challenge, especially trying to sell wine in Chicago.” Schopf said. “People who come here, come back and buy our wine. They understand what we’re doing and can can see it. But, if they’ve never been here, we’re just a Michigan wine – they’re not even ready to taste a great Michigan wine.”

Dablon only started selling their wines to the public in 2015, but Schopf said he has seen the perception slowly changing – like a good wine, he says, the opinions will only get better with time.

“We’re doing stuff that nobody’s done before,” said Schopf, adding the parking lot is often filled with people from northern Indiana – with an increase in traffic from Chicago and Grand Rapids as well. “We’re doing 17 grapes and making over 30 different kinds of wine. It’s a juggling act, but I think it’s worth it.”

For more, visit dablon.com

By Ryan Yuenger

ryany@wsjm.com